December 2014 – January 2015

A CORNUCOPIA IN THE HORN OF AFRICA

In Ethiopia, the year, at the time of this posting, is 2008. The taxi cabs are 50 years old, the calendar has 13 months instead of 12, and the clock is six hours ahead of its eastern Africa time zone. It’s the most mysterious and captivating place I’ve ever been — simultaneously progressive, yet frozen in time.

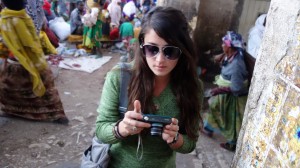

I spent 16 days exploring the central, northern and eastern regions of Ethiopia, from as high up as Chennek in the Simien Mountains, to the deep rock churches of Lalibela. There’s a reason Ethiopia was named “Best Tourist Destination for 2015,” and it remains, to this day, my favourite place to travel. Its cities are crawling with tablet-toting citizens of the world — a minority in a country whose Christian religious traditions are almost as old as parts of the Bible. Each region of Ethiopia has such distinct religious, cultural, and geographic character, and to quote a friend, makes my home country of Canada look like a “cultural pygmy.”

Don’t take my word for it — hop on a plane and see for yourself. From the mixed juice to the gelada baboons, Ethiopia is a cornucopia of offerings for any traveller. And unlike Kenya, its southern, safari-powered neighbour, it’s still a very affordable place to travel. Consider the itinerary below, and as always, feel free to post questions in the comments. I can’t recommend this destination enough.

Day One: Nairobi to Addis Ababa

I was impressed with the grandeur of Bole International Airport. We touched down in the capital on Dec. 20, ready for a last-minute, whirlwind adventure in one of Africa’s best kept tourism secrets. After a lengthy bargaining process with several cab drivers, we were on our way into town, noses eagerly pressed against the passenger windows. Addis Ababa is a wonderful blend of old and new, and our first move in this exciting place was to go for a walk in no particular direction.

PIAZZA

Piazza is an old quarter in Addis and a great place to wander, have a cheap beer, chat with locals, and get a feel for the city. If you take a few turns off the main road, you’ll find elderly women drying peppers and barley in the sun while men crouch on upside down crates, chatting over tiny cups of coffee. Little ones waved as we passed by, shouting whatever English they knew, and giggling when I responded in heavily-accented Amharic. One child followed us, chanting happily on repeat: “There are seven days in the week!” Adorable.

Online reviews might criticize Piazza as “shabby,” “crowded,” and “high in dodgy-ness level,” but that was not my impression in the slightest. I found the neighbourhood to be quite safe and friendly. If you want cleanliness, sidewalks and nice restaurants, check out the financial district, Bole, instead.

Piazza’s name is a legacy of the Italian invasion era, and the neighbourhood prides itself on being centre of Ethiopia’s jazz music movement, which burgeoned between the 1950s and 70s. Our hotel, Itegue Taitu, was not only the oldest hotel in Ethiopia (established in 1898 by the wife of Emperor Menelik II), but a renowned jazz music lounge. Piazza is where most of the budget hotels are located, which makes it a great place to connect with other travellers and enjoy Ethiopian nightlife.

MESKAL SQUARE

Within half an hour, we had walked from Piazza to Meskal Square, a bustling public plaza in the heart of the city where people sit, eat and socialize throughout the day. Here, children sold tissues and sweets from card board boxes, and cab drivers heckled one another as they waited for clients by their iconic blue 1960s Peugeot 404s (took me a while to track down the car model online). Young men did pushups and sprinted up and down the square’s steps, and girls gossiped animatedly, pretending not to watch. Elders sat quietly observing the commotion; Ian and I did the same.

Eventually, we made our way up the steps to the 2014 L’Abyssine International Expo, a trade show of traditional Ethiopian music, food, clothing and crafts. Meskal Square often hosts parades, festivals and events like this one, in addition to the occasional political protest. For more on Meskal Square’s religious and political significance, click here. You can also check out this video, which clearly backs up its claim to fame as “The World’s Craziest Intersection.”

DOWNTOWN ADDIS

From Meskal Square, we walked further into the downtown core. I don’t usually delve too deeply into a country’s history on this blog, but in the case of Ethiopia, it’s hard not to. During the late 19th century ‘Scramble for Africa,’ Ethiopia was the only African country to defeat a European colonial power and retain its sovereignty. In 1974 however, at the end of Emperor Haile Selassie’s rule, Ethiopia’s power fell to a communist military junta known as the Derg, which was backed by the Soviet Union. Tens, and possibly hundreds, of thousands of people were massacred by this regime in a bloody political resistance known as the Red Terror. Famine struck in the years that followed, and the Ethiopia that emerged was forever scarred. Read more here.

While this is an extreme simplification of 20th century Ethiopian history, evidence of this violent past is emblazoned on the streets of Addis today. Walking through downtown core, names like the ‘National Hotel of Addis Ababa’ and the ‘Patriots Building’ served as a reminder of the country’s brush with communism and the state’s looming power over its people. Remnants of Ethiopia’s colonial encounter — a past that nearly became its present — could also be seen in Italian names like Piazza, as well as Italian bakeries, cafés, restaurants, and language schools.

It seemed to me as though Addis had been living inside a semi-permeable bubble for the last 30 to 50 years. New technology, including a high-speed 3G mobile network, had somehow passed through the membrane, yet its age-old framework of 1970s pay phones, 1960s refrigerators, and ancient European cars remained untouched. It was a spectacular juxtaposition that at times, manifested itself in amusing examples of globalization: We found a restaurant called ‘Pizza Bell’ that used the Taco Bell logo, and a sign advertising Ethiopia’s number one ‘Laughter University,’ taught by a local ‘laugh master.’

ETHIOPIAN CUISINE

After long morning of walking in the heat, we stopped for lunch at a hole in the wall near the city’s busy auto shop district. We were the only ferenji (white people) in the house, but no one seemed to mind. I immediately decided Ethiopian was my favourite cuisine: A typical dish consists of sauces, salad, eggs, stewed veggies and meat served on soft, sourdough flatbread called injera. Shiro (chickpeas), wat (stewed chicken, beef or lamb usually), and ful (breakfast beans) are common main courses, eaten with one’s right hand, to be polite. It’s also astonishingly cheap, and at most restaurants or walk-ins on the street, two can fill up for less than 50 Birr (about CAD 2.40). If ever in doubt about where to eat in a new country, go somewhere packed with locals, which is generally a good indicator of value for money. A word to the wise — Ethiopian food doesn’t sit well with everyone’s stomach the first time around, so be prepared for the possibility of a hasty run to the bathroom.

TOMOCA COFFEE SHOP

After lunch, we went for a pick-me-up at the famous Tomoca Coffee Shop on Wavel Street, an old Italian business from 1953 that survived The Red Terror, two famines, and a war with neighbouring Eritrea. It is, by no means, a place to enjoy a traditional Ethiopian coffee ceremony, but serves good espresso and cheap coffee beans to go.

If you’re there, ask to use the bathroom, which will lead you to the back of the café where they keep the big roasting machines. Watch out for the cockroaches, which scurry freely through the establishment. Tomoca is worth a visit just to be among the young, up-and-coming of Addis, who visit the old colonial café as a mark of wealth and status. There’s also a random moose head on the wall, sculpted by someone — in my opinion as a Canadian — who has clearly never seen a moose.

NIGHTLIFE

As the sun dipped below the horizon, we returned to Piazza. Addis lights up at night and Piazza is packed with bars, restaurants, clubs and jazz lounges frequented by locals and backpackers alike. We planned to eat at the internationally-acclaimed Castelli Restaurant for dinner, but in the end, opted for a local dive. We paid roughly 60 Birr for a massive plate of wat and injera, then hit up a few of the clubs on the strip.

This was some of the best bar-hopping I’ve ever done — beer ranged between 12 and 20 Birr (less than USD 1) per bottle, and the mix of modern and traditional Ethiopian music was refreshing. At a particularly lively hole in the wall, we made friends with an upbeat, Kenyan-Ethiopian named Thomas who regaled us with family stories when we told him we had come from Nairobi. Feel free to dance in Ethiopian clubs (conservatively) and make sure you ask someone to teach you how to dance traditionally. They’ll be happy to show you Ethiopia’s signature step, a kind of dipping shoulder shrug, often danced in a circle with friends. If you’d like to see more traditional dancing, the Yod Abyssinia Cultural Restaurant in Mekanisa hosts nightly performances.

Day Two: Addis Ababa

Our second day kicked off with some unexpected action. After wandering around Piazza for a while, Ian and I found a little shop serving breakfast next to a group of boys playing soccer on the street. We paid 20 Birr for a mountain of spaghetti on injera, which we ate by hand as we watched the game, cheering on players who had, of course, named their teams after Premier League favourites.

I had remarked to Ian the previous day that nearly every open space in Addis has been converted into a makeshift soccer field, and the skills demonstrated by neighbourhood youth playing on cobblestone, in flip flops, was remarkable. I couldn’t resist the urge to join in for the second half, tomato sauce-stained hands and Crocs and all.

NATIONAL MUSEUM

Having been sufficiently put to shame on the pitch, we walked back towards Meskal Square to catch a minibus (3 Birr) to the National Museum of Ethiopia on King George VI Street (entrance is 20 Birr per person).

I had been looking forward to this since we landed in the capital — the national museum is home to Lucy, the 3.2 million-year-old australopithecus skeleton that practically rewrote human history. Ethiopia is widely recognized as the birthplace of modern humans, and the museum has an impressive collection of bones from other early humans and prehistoric animals.

Though poorly lit, poorly maintained and poorly labelled, its exhibits from the pre-Aksumite, Aksumite, Solomonic, and Gonder periods contained impressive artifacts. I was floored by the opulent possessions of early Ethiopian royalty, and the intricacy of their traditional clothing and jewellery. The relics — bronze coins, ancient utensils, furniture, and art — were spectacular, and English-speaking tour guides were happy to explain the artifacts in exchange for a modest tip.

HOLY TRINITY CATHEDRAL

We could have spent hours walking back from the museum, stopping at Africa Hall, the Parliament Building, the University of Addis Ababa, and the National Palace, which are all on the way to Meskal Square. But with only one more afternoon in the capital, we gave them a miss, opting to take our time at the Holy Trinity Cathedral by Niger Street instead.

The Holy Trinity Cathedral is the second most important place of Christian worship in Ethiopia, and at any hour of the day, followers can be seen kissing and caressing its walls, kneeling at the gates, praying on the steps, and reading scripture in the garden. Ethiopians follow a unique brand of Orthodox Christianity, somewhat related to the Egyptian Coptic church, which they branched off from nearly 70 years ago. What’s special about this faith however, is that it comes from the age of the Bible (not from European colonialism) beginning as early as 330 AD.

The Holy Trinity Cathedral is the final resting place of Emperor Haile Selassie and his wife, Empress Menen Asfaw, whose impressive Aksumite-style granite tombs can be viewed inside. Entrance is 50 Birr per person and includes access to a small museum of church artifacts and the cathedral’s graveyard, where ministers killed by the Derg and patriots who died fighting Italian occupation are buried.

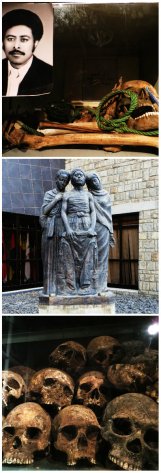

THE RED TERROR MUSEUM

Our next stop was the Red Terror Museum on Bole Road. We paid 20 Birr for a cab from Meskal Square to its doorstep, where a statue of mourning women etched with the words, “Never, Ever Again,” foreshadowed the harrowing exhibits within.

The Red Terror Museum is not for the faint of heart, but is a must-see for all visitors to Addis Ababa. It spares its guests no gruesome detail in its commemoration of what many consider to be a “modern day Holocaust.” Inside we found the names, body parts and personal effects of many victims, along with the devices used to torture them before they died. The facts surrounding the slaughter of up to 500,000 Ethiopian men, women, and children at the hands of the Derg are highly contested due to lack of data, but one item is undeniable: Thousands of innocent civilians were brutally massacred under the guise of “building a better Ethiopia” by a twisted junta that seized illegitimate power.

All the tour guides at the museum are survivors of this tragedy and earn a living by reliving these horrific events for dozens of visitors everyday. Their wounds are reopened time and again as they go over pictures of families and friends on the walls — an incredible sacrifice made in the hope that history will never repeat itself. Entrance fees are by donation, and I encourage you to give generously in order to preserve this vital piece of the past.

ST. GEORGE’S CATHEDRAL

The exhibits had their intended effect and we left the Red Terror Museum with knots in our stomachs. The 50-minute walk to St. George’s Cathedral helped clear them, but underlying feelings of sadness lingered with me for the rest of the day.

St. George’s Cathedral is a bit out of the way for tourists, but worth dropping by for its proximity to Menelik II Square. It was completed in 1911, commissioned by Emperor Menelik in honour of his defeat of the Italian occupation in Adwa in 1896. Its outer walls are covered in beautiful paintings and mosaics, and religious merchants draped in traditional white Orthodox clothing sat by its gates selling ecclesiastic souvenirs — wooden crosses, stones, necklaces and Bibles. I learned that the cathedral is a popular detour for many commuting Ethiopians, who stop by, kiss its walls and pray on their way home from work if they didn’t have time to attend service that day. Having already paid enough entrance fees for the afternoon however, Ian and I decided to skip a tour of the church interior and people-watch in the square instead.

MENELIK II SQUARE

Menelik II Square is another bustling public plaza in Addis where people sit, eat, drink, and chat. A massive equestrian statue of the emperor rests in its centre, marking the spot where all major highways in Ethiopia meet.

One particular image in the square struck me: massive Pepsi ads plastered near a group of retro coach buses. Coca-Cola had a monopoly on every African country I had ever been to, where its products are sold (despicably) cheaper than drinking water. But here, in Ethiopia — a country that carefully restricts outside influence — Pepsi had managed to stake its claim. I celebrated a small, private victory — for a number of reasons, I’ve never been a fan of the Coca-Cola empire.

HAGER FAKIR THEATRE

A hop, skip, and a jump away from Menelik II Square is the historic Hager Fakir Theatre. Founded in 1935, it’s the oldest indigenous theatre in Africa, and represents more than 70 years of development in Ethiopian music and drama. The company survived the Italian occupation, and today runs both traditional Ethiopian plays and translations of European playwrights by Shakespeare, Schiller, Ibsen and Molière. We walked into the compound to take a few photos, but were quickly shooed out by a group of actors and staff sitting by the theatre doors. I’m not sure why they were upset, but we made a hasty exit. Don’t let this discourage you from trying to see it, but don’t sweat it if you miss it either. The theatre itself is underwhelming, despite its intriguing history.

SAYING GOODBYE TO ADDIS

We spent our last evening in Addis wandering around Piazza, taking photos and jotting down all the little things we wanted to remember: The dogs that sat in the middle of every intersection, and the catchy electronic tune played by the men who had scales you could weigh yourself on for 1 Birr; I wanted to remember the toddler who danced hand in hand with her father at L’Abyssine International Expo, and Thomas, the Kenyan-Ethiopian who had beer with us at the nightclub.

One particularly amusing anecdote stands out — a baby, tucked in her mother’s lap on the street, innocently tossing their coins into the sewer as his mother looked elsewhere, hands outstretched to passersby. We tried to tell his mother about his little game, but she didn’t understand us.

Later that night, a group of men invited me to join them for coffee. They didn’t speak much English, but through a combination of broken Amharic, French, and Swahili, we managed to exchange basic pleasantries. Ethiopia is among the friendliest countries I’ve been to, and as these gentlemen wished me well for the evening, (“Dehna hunu”) I made sure to jot them down in my notebook along with Thomas, the toddler, and all the others.

Know Before You Go — Addis Ababa

Travel Tips

- Tourist visas can be purchased on arrival at the airport in Addis for USD 50. Bring exact cash — there are no ATMs or banks on this side of the gate and you WILL be stuck without it.

- If you walk past the yellow airport cabs in the parking lot, you can hop in a blue one for much cheaper (30 Birr to Piazza). Alternatively, there is a minibus station under the freeway to your right that can take you to Piazza for 3 to 5 Birr.

- Exchange your currency with the hotel touts in the lobby. They’ll give you a better rate than the bank.

- Buy a local SIM card and data package for your phone — you’ll be grateful for the ability to look up attractions, consult maps, use the GPS, and book hotels on the fly. Plan to spend a few hours accomplishing this; cell phones are strictly controlled by the government.

- Bring an Amharic phrase sheet with you to Ethiopia. English is not widely spoken and you may have trouble ordering food or asking for directions (it’s also basic courtesy to show up knowing how to greet, thank, and ask politely).

- Two days is enough to see all of Addis’ major attractions including historical sites, museums, and political buildings. My recommendation however, would be that you choose a few that are important to you, and spend the rest of your time wandering, and getting to know the city.

- We managed to book most of our hotels in Ethiopia as we went, despite having travelled during peak tourism season. Don’t stress too much about planning everything in advance.

Where to Stay

- Itegue Taitu Hotel is a safe, centrally-located backpacker in Piazza. We paid roughly 300 Birr (USD 15) per night for a self-contained double bedroom with only one working power outlet and no toilet paper. The conditions won’t be much better at any other backpacker, so if you’re looking for a bit more comfort, try a nice hotel in Bole. I stayed at the pricey Nexus Hotel there during a layover on the way home (on Ethiopian Airlines’ dime of course), and was very pleased with the rooms and service.

- NOTE: Taitu burned down in a massive fire only weeks after I stayed there — a real loss to Ethiopian heritage. It is scheduled to be rebuilt, but I recommend the nearby Ankober Guest House (+251 111 562 878) or Baro Hotel (+251 111 551 447), both of which are comparable in price and amenities, until Taitu reopens.

Day Three: Addis Ababa to Debark

I’ve always been a fan of travel by road, for the scenery, time alone with my thoughts, and ability to make last-minute stops for whatever intriguing opportunity arises. Ethiopia however, is not an easy country to cross by bus or by car, and intercity travel through its national airline is so cheap, there really is no better alternative if you’ve only got two or three weeks.

Our plane landed on time in the northern city of Gondar, above Tana Lake in the Amhara Region. Our tour co-ordinator, Bocata, was a stylish and spritely young man in his mid-20s, and waiting for us at the airport with a vehicle. We negotiated our all-inclusive hike through the magnificent Simien Mountains (less than CAD 450 each), and a two-night stay at the L-Shape Hotel in Gondar.

After a short ride through farmland, we arrived at the hotel where Bocata introduced us to Aitor, Juho, and Grace, three tourists who would be hiking with us. All aboard a rickety van, we started the beautiful two-hour drive to Debark, the entrance point for Simien National Park. There, Bocata hired a local scout and picked up Lej, our mountain guide and escort through the “Roof of Africa.” We were dropped off on a dusty road in the middle of nowhere, and Lej pointed to the winding path ahead. There was nowhere to go but up, so we slung our backpacks around our shoulders and started our adventure.

Day Three to Seven: Simien Mountains

The Simien Mountains are a mountain range of overwhelming natural beauty, whose ecological and geographical diversity are practically unparalleled. Rippling highlands, peaks, and plateaus prelude stunning high altitude scenery of palm trees, old growth forest, and barley, where ancient Amhara tribes live the same way their ancestors did a thousand years ago.

In between glorious sunsets and tumbling waterfalls, we were privileged not only to meet some of these residents, but to enter their homes for a traditional Ethiopian coffee ceremony. Along the way, we bumped into the socially adventurous gelada baboons, the rare walia ibex, and several species of eagle and falcon.

I chronicled the adventure for the Globe and Mail’s travel section — every detail from the food we ate to the people we met. I left out the part where I helped the cooks slaughter a goat for dinner, but the account is otherwise accurate. It also includes a breakdown of the logistics; what to pack, how to get there, where to stay, and how to book your own hike for less than CAD 450. We couldn’t have been happier with Bocata’s services, and he has given me permission to share his contact details. Feel free to call him at +251 918 789 242 for information on arranging a tour.

THE PHOTOS

Day Eight: Gondar

We made it back to Gondar on the fourth day of our hike just in time for Christmas. Around this time of year, the city’s markets are peppered with holiday decorations including trees, tinsel, and plastic baubles. Gondar is a busy place, home to roughly 360,000 permanent residents. Wandering around, we often found ourselves dodging rickety tuk tuks on the streets, which are also shared with herds of livestock jogging at the behest of their switch-carrying masters. Gondar is a fine mix of urban and rural living; a chaotic city of craftsmen, farmers, university students, and people who scrape a living out of everything from selling sweets on the streets, to hosting strangers for shisha and televised soccer matches in their homes (we partook in the latter).

It was here in Gondar that Ian and I discovered the most exquisite beverage of all time: an avocado, mango, and passion fruit phenomenon called ‘mixed juice,’ which we shamelessly drank at least twice a day for the remainder of our trip. We also found our new favourite pastime in Ethiopia — hopping between local cafés to drink tea, play cards and people-watch. This was eye-opening; we saw as many young couples in love, seniors reading the news over coffee, and fashionable teenagers as we did ill beggars, starving families, and homeless, khat-addicted children staggering through the streets. Plan to spend at least a day and a half in Gondar.

FASIL GHEBBI

Gondar was once the capital of Ethiopia — the heart of trade and agriculture under the rule of 17th century Emperor Fasilides. During his reign, the great king constructed Fasil Ghebbi, a fortress city with a 900-metre wall that would house his family, descendants and visiting emperors. The remains of its castles and palaces earned Gondar the title, “Camelot of Africa,” and in 1979, Fasil Ghebbi was named a UNESCO World Heritage site.

The fortress city functioned as the centre of the Ethiopian government until 1864, and its architecture “represents a remarkable interface between internal and external cultures, with cultural elements related to Ethiopian Orthodox Church, Ethiopian Jews and Muslims,” (UNESCO). We spent at least an hour exploring these ruins; the crumbling turrets, the tiny windows, and the remains of enclosures for leopards and lions that used to grace the palace grounds. Fasilides’ Castle itself is the most well-preserved site, and while we guessed what the buildings might have looked like during their heyday, you can hire a local tour guide on site to tell you for a nominal fee.

We paid 200 Birr for entrance, which included Fasilides’ Castle, the Castle of Emperor Iyasu, the Library of Tzadich Yohannes, the Chancellery of Tzadich Yohannes, the Castle of Emperor David, the Palace of Mentuab and Banqueting Hall of the Emperor Bekaffa.

FASILIDES’ BATH

Our entrance fee to Fasil Ghebbi also covered the great king’s swimming pool, which is located outside of the fortress, northwest of the Qaha River. You can take a tuk-tuk there for roughly 20 Birr from the heart of the city, and show them your receipt from the castle for entry.

Fasilides’ Bath is a two-storey palace in the centre of a square pool that is usually kept empty for sanitary reasons, but filled by the river for special rituals like Timket, the Ethiopian celebration of the Epiphany. During Timket, thousands of Ethiopian Orthodox Christians pore into Gondar to renew their baptismal vows during a symbolic reenactment of the baptism of Jesus. The bath is quite a sight to behold, if not for its remarkable size and structure, for the strange, winding trees roots that grow around its ledges.

DASHEN BREWERY

We had paid our tuk tuk driver roughly 60 Birr to take us from Fasil Ghebbi to Fasilides’ Bath, and eventually to the Dashen Brewery. We were hoping for a tour, but upon finding it closed to the public for the day, settled for pasta and a pint instead. Dashen is currently the second largest brewing company in Ethiopia by capacity, the youngest major brewery (built in 1996), and the only brewery that strictly adheres to German purity laws on the ingredients of beer. At first, it was one of our favourites, but it quickly sunk to the middle of the pack in our list of favourite Ethiopian beers for its rather bland, pale ale taste.

Despite its strong roots in traditional Christianity, Ethiopia has a robust national beer culture that consists of a dozen or so popular brews. In true reflection of the country’s religious ties, St. George takes the cake as the national favourite, its bottle bearing a red and yellow label depicting the third century Roman soldier who slayed a fire-breathing dragon in ancient Christian legend. Ian and I sampled most of the country’s drafts during our 16-day trip, listed below in order of preference. This will help if you want to be selective during your drinking spree, but at prices ranging between 12 and 20 Birr a bottle, why bother?

- Hakim Stout 7. Meta Premium

- Harar Beer 8. St. George

- Meta Beer Export Lager 9. Bedele Special

- Royal Beer 10. Castel Beer

- Dashen Beer 11. Walia Beer

- Amber Beer

To learn more about Ethiopia’s burgeoning beer market, click here.

FOUR SISTERS RESTAURANT

After lunch at the Dashen Brewery, we spent the rest of our afternoon exploring the city by foot. We ‘tea-hopped’ at several cafés, where as per tradition, our tea and coffees were served to us on a bed of grass, accompanied by seeds or sugared popcorn.

We did a loop of neighbourhoods near the Ibex Roundabout, and ran into the same little boy selling sweets from a box over and over, and over again. We had bought gum from him the previous day when we got back from our hike (banana and strawberry were my favourites), and after that we couldn’t shake him. We ran into him at breakfast, during the afternoon and evening — either he had been following us, or Gondar was such a small place that two ferenji were easy to find. I can’t remember his name now, but I remember that he was 10 years old, spoke very good English, and worked seven days a week to earn money for his family. He told us he was in school full-time, and did his homework late at night once he finished selling all his gum. We didn’t need any gum at the time, but paid him a whopping 10 Birr (barely 50 cents, but enough to buy half his box of sweets) for giving us directions to the Four Sisters Restaurant instead.

The Four Sisters Restaurant is a little tricky to find on your own (especially in the dark), but it’s worth the commute if you missed out on traditional Ethiopian music and dance in Addis Ababa. The restaurant caters itself to tourists, and if you’re tired of worrying about getting sick from street food, the Four Sisters is a place of respite. It’s a tad overpriced, and a little inauthentic in terms of its excessive display of culture, but the fasting plate (meaning vegetarian) was good, and the tej (honey wine) was sweet. After dinner, Ian and I had shisha in someone’s living room down the street from our hotel and watched the Premier League match on television. We made awkward conversation with the other men in the room, most of whom were high from khat and passing around a box of cigarettes

Day Nine: Gondar to Aksum

WOLLEKA VILLAGE

Our flight to Aksum wasn’t until 4 p.m., so we made the most of our last day in Gondar. After a quick breakfast of ful, egg and croissant, we caught a tuk tuk to Wolleka Village (15 Birr), roughly three kilometres north of the city. Wolleka is the main centre of Beta Israel — Ethiopian Jews — who are also known as Falasha. Though most of the Falashas were flown to Israel in the 1980s, a few Stars of David, a small synagogue and a graveyard remain in their old village today. According to Lonely Planet, Falashas were once great craftsmen, forced to take up pottery and other trades after their land was confiscated during Ethiopia’s conversion to Christianity. Research suggests they may have even provided the labour for the construction and decoration of Gondar’s castles, but “sadly, the pottery for which they were once famous has mostly degenerated into half-hearted art.”

Wolleka is indeed full of cheap trinket, and craft shops, but if you’re looking for a product of quality, check out the Project Ploughshare Women’s Crafts Training Center in the village. The initiative helps disadvantaged women rekindle the arts and crafts of their ancestors, including traditional Amhara weaving, basketry, and pottery. If you can’t find the centre, one of the local children will be happy to offer directions for a few Birr. In fact, expect an entourage of persistent sales children everywhere you go in Wolleka — Ian and I were followed around for the better part of an hour before shaking the kids off to catch a minibus (3 Birr) back to Gondar.

DEBRE BERHAN SELASSIE CHURCH

When we got back to the city, we hired another tuk tuk (20 Birr) to take us to the Debre Berhan Selassie Church on the eastern outskirts of town. I knew this church was a major attraction in Gondar, but had only skimmed over its description, and couldn’t remember exactly why. The reason was immediately obviously when we entered the compound — built in the 18th century, Debre Berhan Selassie is considered one of the most beautiful churches in all of Ethiopia.

Twelve stone towers (one for each apostle) guard its gates, which are marked by a taller, 13th tower representing Christ himself. An ornament of seven ostrich eggs (mirroring the seven deadly sins) decorates the doors, and the church interior is even more elaborate: Paintings cover the walls and ceilings, including 135 winged cherubs, an image of St. George slaying the dragon, and a depiction of the devil leading Prophet Mohammed into the fiery depths of hell. When Mahdist Dervishes of Sudan sacked the city of Gondar in 1888, they burned down every church except Debre Berhan Selassie, and according to local legend, a swarm of bees kept the soldiers at bay while the Archangel Michael himself came down from Heaven to protect it with a flaming sword.

Though Debre Berhan Selassie Church is technically part of Fasil Ghebbi, its keepers charge separate entrance fee of 80 Birr per person. On the compound, I met a travelling Irish sketch artist who was copying it in his notebook and a young Ethiopian man studying from an ancient Bible near the church patio. I asked him about his studies, and he told me the Bible was an heirloom passed down from his father, who had recently passed away. The 19-year-old’s dream was now to become a priest and offer service at the beautiful church, where his father prayed every day. I shook his hand, wished him luck in his endeavour, and within two or three hours, waved goodbye to Gondar.

Know Before You Go — Gondar

Travel Tips

- See my piece, Scaling Simien: Budget mountains for beginners in Africa, for tips on hiking the Simien Mountains.

Where to Stay

- There aren’t too many accommodation options in Gondar, but the L-Shape Hotel is comfortable, clean, and inexpensive at 280 Birr (USD 14) per night. They can keep your luggage safe while you hike or explore, and have a great bar and restaurant in the lobby. Centrally-located, within walking distance of most attractions.

ARRIVING IN AKSUM

We landed in Aksum by early evening on the ninth day of our journey. At this point, we were a bit worn out and looking forward to a quiet evening of dinner, mixed juice, and perhaps a beer. Unfortunately, the airport experience was a bit aggressive — from the moment we stepped off the plane, we were hustled by tour and hotel operators, who were eager to charge us inflated transportation rates to take us to the city, and more directly, the doorsteps of their employers. After a bit of haggling, we settled on 16 Birr each for a minibus ride into town that would drop us off at the Africa Hotel on the main drag. We checked in, and as usual, marched straight out the door for a good, long walk.

Despite being home to more than 56,000 people, Aksum was by far the quietest city I visited in Ethiopia. Restaurants and cafés on the main street twinkled brightly with Christmas lights, but the evening hubbub of Gondar and Addis simply wasn’t there. Young people held hands and walked down the street, old friends caught up over cups of coffee, and others read books in the gardens of Ezana Park. Following their lead, Ian and I pored over trip photos quietly as we ate spaghetti and shiro at a nearby restaurant. On the way back to the hotel, I ended up in heated negotiation with a young man named who approached me on the street offering tuk tuk transportation between Aksum’s ruins for 600 Birr per day. He assured me that these sites were “very far away” and couldn’t be reached easily on foot, but I had read otherwise and sensed a scam. He texted me until 11 p.m. that night trying to broker a deal, and even dropped the price to 230 Birr. Be warned — the tourism industry is pushy in Aksum, especially when visitors are scarce during low season.

Day 10: Aksum

OLD QUARTER

Despite the young man’s advice the previous evening, Ian and I had firmly settled on touring Aksum by foot. It was a beautiful day, and after grabbing bread and bananas at a little shop on the road, we made our way to the Old Quarter of the city, which surrounds the Northern Stelae Field and stretches west to Ta’akha Maryam.

It was much like stepping into a time machine — with crumbling residences and dusty dirt roads, there wasn’t much differentiating this neighbourhood from the historic ruins two or three blocks away. Teeming with goats, mules and chickens, it certainly bore no resemblance to the manicured main road we had explored the previous evening, where we had eaten spaghetti and browsed online through the hotel’s 3G network. Here, veiled women huddled in groups, children snuck peeks at us through stone windows, and men carried their wares — produce, firewood and livestock — to market. A 20-minute walk separated these two vastly different worlds, and as Lonely Planet writes, the Old Quarter serves as a reminder that Aksum is “more than just a collection of dead ruins; rather it’s a living, breathing community where the past persists.”

Aksum is one of the oldest continuously inhabited places in Africa, and dominated the region as a naval and trading powerhouse from around 400 B.C. to the 9th century. Its kingdom was the most powerful state between the Eastern Roman Empire and Persia, and despite its political decline in the 10th century, Ethiopian emperors continued to be crowned there for many years. Massive ruins, dated between the 1st and 13th century, are all that remains of these glory days, and after exploring the Old Quarter, we made our way to the grandest of them all.

NORTHERN STELAE FIELD

Aksum was declared a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1980 as a symbol of the wealth and power of the old Ethiopian kingdom, and a crossroads between Africa, Arabia and the Greco-Roman world. The Northern Stelae Field — only 10 minutes past the Old Quarter — is one of the best examples of how this ancient society flourished, and has a set of remarkably intact third and fourth century obelisks. The field is a treasure trove of mystery; no one knows exactly why the obelisks were created, how they got there, or what ruins remain undiscovered beneath the ground. Only 10 per cent of the site has been excavated and parts of it remain off limit while digging continues.

Highlights of the stelae field include the Tomb of the False Door, the Mausoleum, the Tomb of the Brick Arches, the Tomb of Nefas Mawcha, and a stunning 33-metre obelisk, likely the largest monolith stela that ancient humans ever attempted to erect (it fell to the ground between the 3rd and 4th century). Most of the tombs were looted by robbers long ago, but locals still believe that beneath one of the graves lies a ‘magic machine’ that the Aksumites used for melting the stone that shaped the stelae and tombs. Another popular legend is that the obelisks — phallic in shape — are ancient symbols relating to fertility. Entrance is around 100 Birr, and includes access to the Archeological Museum next door, which is worth checking out for its detailed descriptions of Ethiopian monarchical and religious history, old stone artifacts and pottery.

CHURCHES OF ST. MARY OF ZION

From the Northern Stelae Field, we walked a short distance to the Churches of St. Mary of Zion. I didn’t fancy parting with another 200 Birr for admission, but this was another site in Aksum we simply couldn’t miss. There are two churches on the compound, an older one for men only and a newer one for both women and men. The former was built by Emperor Fasilides in 1665 and mostly contains old murals, while the latter was built in the 1960s to the decorative tastes of Emperor Haile Selassie (think brightly-coloured paintings, tacky ornaments and fake flowers).

It is said that this compound is “the centre of the universe for Christian Ethiopians,” and that a church in some form or another has stood there since the very start of Ethiopian Christianity. In fact, many believe God himself descended from the heavens nearly two thousands years ago and indicated that a church should be built in that very spot. We explored the compound for nearly an hour (followed by one male worshipper, who for some reason, seemed to believe we were up to no good), and sat quietly in the pews of the newer church as white-clothed pilgrims came to pray.

The real reason for these pilgrims’ devotion, however (and my insistence on paying the entrance fee) lies between the old and new churches: A small, carefully-guarded chapel that supposedly contains the legendary Ark of the Covenant. I’m almost certain my heart skipped a beat when I first laid eyes on it — as a lifelong Indiana Jones fan with an interest in religious history, it was a special (albeit anticlimactic) moment. The repository, unfortunately, is not much to look at from the outside, and no one is allowed within 100 feet of it.

I took a photo, glanced longingly for several minutes and made my way to the museum next door, which contained a magnificent collection of church wealth, including former Ethiopian rulers’ crowns, precious chalices and crosses. Museum guides there will expect a tip. Still stunned by how underwhelming the chapel (allegedly) containing such an overwhelming item was, I browsed the rows of ancient Bibles and church robes in the museum, asking myself whether I believed it was in there. Ethiopian legend has it that the Ark was stolen, with God’s will, from the Temple of Jerusalem by Melenik I, Solomon’s own son by the legendary Queen of Sheba, and brought to Aksum as its final resting place.

PALACE OF QUEEN SHEBA

After the Churches of St. Mary of Zion, we walked to the Dungur Palace, also known as the Palace of Queen Sheba. Stone foundations are all that’s left of this once grand, 7th century structure, which despite its nickname, was actually built about 1,500 years after the time of Queen Sheba. Historians believe it was once the mansion of a nobleman, and through sloppy restoration you can make out 44 different rooms, including a bathing area and kitchen where a large brick oven still sits.

I recommend hiring one of the guides on site to take you around the ruin, as the rooms (apart from the kitchen and bathroom) contain no artifacts or structure that indicates their purpose. Without someone to explain and illustrate the palace for you, harshly speaking, it’s a three-foot-high foundation of relatively unimpressive rocks. There are some neat trinkets for sale outside the entrance however, and the Judith Stelae Field (not worth your time if you’ve already seen the Northern Stelae Field) is right across the street in what looks like a roped-off corn field.

LIONESS OF GOBODURA

The walk to Queen Sheba’s Palace was much further than we had anticipated, and not to keen on walking much further, we called a tuk tuk driver to take us to the famous Gobodura Hill. The hill, roughly 1.5 kilometres past the palace, is one of four ancient quarries in Aksum that birthed the granite stelae found in the city. Several stelae (all unmarked) are still abandoned there, and as I mentioned, it’s still a mystery how in the 3rd and 4th centuries, ancient Aksumites managed not only to cut these rocks, but transport hundreds of tonnes of them back into town.

After about 20 minutes of climbing through brush and boulders (and repeatedly assuring us he knew where it was) our tuk tuk driver finally found the remarkable stone carving of the Lionness of Gobodura. According to Christian stories, it was here on Gobodura Hill that the Archangel Mikael fought a mighty battle with a fierce lioness, a battle that only ended when he hurled it into a massive boulder, killing the beast on impact. Such was the force of his throw that the outline of the lioness is still visible on the rock that it hit.

The other theory of course, is that it was carved around the 3rd century, when people started adding carvings to the nearby stelae. We paid our driver 130 Birr for all of his time, including a drop-off in the Old Quarter. Note that while you can walk to Gobodura Hill (about an hour round trip), you won’t be able to find the carving on your own. There are usually a few children kicking around however, happy to take tourists there for a few Birr.

SAYING GOODBYE TO AKSUM

It’s unfortunate that despite a long day of touring — and some very impressive historical ruins — none of Aksum’s attractions had the same shock and awe factor for me as the tiny chapel that allegedly contained the Ark of the Covenant. I laugh about it today; I was so enchanted by an object I hadn’t even seen. Perhaps that’s the effect of Hollywood movies, or the illuminating tale of its contents written in the Old Testament. Either way, Ian and I spent our last few hours in Aksum wandering the Old Quarter, drinking mixed juice, and browsing the market for souvenirs, sunglasses, and whatever knick knacks caught our eyes. Our wandering eventually led us to the fancy hilltop Yeha Hotel, where we pretended to be guests so we could sit on the balcony and watch the sunset. We stayed until dark, and ended our evening at the colourful AB Cultural Restaurant in town, which is a nicely-decorated place to eat, but average in terms of taste and price.

Know Before You Go — Aksum

Travel Tips

- Prepare to be hustled almost everywhere in Aksum, especially by drivers and hotel touts.

- You can walk to most of the attractions in town, but to get to the Palace of Queen Sheba, the Judith Stelae Field and the Lionness of Gobodura, you can catch a minibus heading towards Shire for 3 Birr, or you can hire a tuk tuk from Aksum for between 60 and 150 Birr round trip. Expect to haggle heavily for this price.

- While I truly enjoyed Aksum — the Old Quarter and St. Mary Church of Zion especially — it didn’t have the same warmth, charm, or exciting vibrancy of the other places in Ethiopia I visited. I’m glad I went, but if you’re on a really tight schedule, you might want to consider skipping it. Lalibela is much more impactful in terms of religious and historical wow factor and will satisfy your craving for ancient ruins.

Where to Stay

- The Africa Hotel (+251 347 753 700) has plain and simple double occupancy rooms at a modest rate of around 250 Birr per night. The showers, sinks, and toilets work, which is all you can ask for at a cheap Ethiopian hotel. WiFi is included, and the lobby restaurant isn’t bad either. I also recommend the Atse Kaleb Hotel (+251 347 752 222) as a nearby and comparable alternative.

Day 11: Aksum to Lalibela

Despite its remote location, Lalibela is the star of Ethiopia’s tourism industry. Rightly so — it’s the second holiest city in the country after Aksum and the final destination of an annual pilgrimage that attracts more than 50,000 Ethiopian Orthodox Christians. This was the only place Ian and I ran into a significant number of other tourists, who like us, were hoping to catch the peak of the Christmas pilgrimage. We rattled through the mountains into the city, stopping briefly for pictures of the spectacular landscape and to buy handicrafts from women and children who waited on the shoulders of rural roads.

The town itself was quite a sight: Youngsters ran frantically through the dusty streets chasing ragged soccer balls, teens scrubbed the shoes of strangers with dirty water for few extra Birr, and men, full of food, lounged with their pants unbuttoned in the plastic chairs of juice bars. Chickens scurried through the neighbourhood, dogs slept in heaps by burning garbage, and almost every home had a sign on the door advertising “traditional Ethiopian coffee ceremony” for tourists. It was clearly a place accustomed to visitors, and I couldn’t wait to start my walk. I left Ian at the hotel to do some work, then hit the streets for a breath of silty Lalibela air.

Lalibela is a small city. Venturing into some of the residential areas, I was playfully chased by children, one of whom cried frightfully when I chased him back (either he didn’t know how to play tag, or I was the most terrifying ferenji he had ever seen). I was invited for beers by a group of young men who were running their parents’ curio shop, hoping I could break up the monotony of their day by telling them a few good North American jokes. I left when they started pestering me for money to pay for their textbooks, only to walk straight into a group of tour guides pestering me to hire them for a day at the rock-hewn churches. Annoyed, I walked straight out of town until I found an out-of-the-way place to have lunch.

Half-way down the hill south of city centre, I found a small family restaurant hidden in the bushes, its yellow sign barely visible to passersby. I was greeted by a man in his early 30s named Abayneh, who couldn’t have been more thrilled to have someone — anyone — walk into his business and order a plate of food. Although I ended up sharing most of my shiro and injera with restaurant’s the scrawny kittens, I had a delightful conversation with Abayneh, who kept bringing over Dashen beers, and refilling my shiro from a pot over a coal fire in the backyard. We talked about government suppression in Ethiopia, the country’s deplorable human rights record (which persecutes journalists in particular), and how Ethiopia is one of “the richest poor countries in the world.” Despite its strong currency, and a GDP ranking among the highest in Africa, the vast majority of Ethiopian citizens are poor. As as the sun started to set, we shook hands warmly, and I left the restaurant on the promise I would return for another chat before leaving Lalibela.

When I got back to the hotel, my friend Ian had finished his work and was ready to go for a walk. We had mixed juice at a nearby parlour and ended the day with dinner at the Blu Lal Hotel restaurant in town, where we caught up on the news through its small tube television.

Day 12: Lalibela

We woke up around 7 a.m. on (Western) New Year’s Eve to be first in line for permits to Lalibela’s famous monolithic churches. The ticket office is tricky to find, so it’s best to get directions the day before you actually need to be there. It’s pretty hectic in the morning as tourists rush in and you’ll be hassled by guides hoping for work if you don’t look like you know what you’re doing. Single-day permits are USDS 50 each (bring exact cash) and all proceeds go to the continued care and restoration of the churches.

Down to business: I can’t even begin to explain the spellbinding magic of this UNESCO World Heritage Site. There are some things even a journalist can’t describe in words, and if you have a travel bucket list, put Lalibela at the top.

ROCK-HEWN CHURCHES OF LALIBELA

Deep underground in Lalibela are 11 medieval cave churches carved from red volcanic stone under King Lalibela in the 13th century. When Muslim conquests halted Christian pilgrimages to the Holy Land, he wanted to build a ‘New Jerusalem’ for Ethiopian Christians — somewhere they would be safe to worship, hidden from Muslim invaders in the north. His men built the 11 stone churches, chiselled by hand into single ‘mother rocks,’ some as deep as 63 feet. If you look closely in these churches, you’ll even see the scratches of the chisels used more than 800 years ago.

As Ian and I descended the steps into Bet Medhane Alem, the largest church, we found hundreds of pilgrims already crowded in the pit, circling the church, kissing its walls, caressing its foundation and crumbling doorframe. Some bore traditional religious facial tattoos and others had crossed their foreheads with chalk. Most wrapped themselves white cloth and carried walking staffs or Bibles. All had abandoned their footwear, exposing cracked, dry and blistered feet.

An essential part of the Lalibela pilgrimage is walking there, and it is said to pray at the steps of the great stone churches is to earn seven generations of blessings for your family. Through a translator, I spoke with a pilgrim in her late sixties, who had walked there from north of Gondar — a distance of more than 400 kilometres — over the course of a month. Like most who make the journey, she was very poor, and relied heavily on the charity of towns along the way. She told me she “could die in peace now,” knowing she had completed her pilgrimage, and my translator told me this was typical of Ethiopian Orthodox Christians: They are groomed from birth to treat the pilgrimage as a kind of “life’s work,” and getting to Lalibela is the ultimate goal. Every year, youth volunteer at the entrance of the city with cloths and buckets to wash the feet of arriving pilgrims, and provide basic humanitarian relief. I was astounded by everything they told me, and humbled by their devotion.

Inside Bet Medhane Alem, we found old paintings and relics, and three large rectangular holes in the ground. These empty graves are said to be the symbolical tombs of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, and on Sundays, worshippers come here to be healed or blessed by a 7kg gold Lalibela Cross inside the church. All of the churches are connected through a network of underground tunnels that allow pilgrims to move around undetected. These passages, pitch black and difficult to navigate, are a representation of hell, and when a pilgrim surfaces into light on the other side of one, it’s a symbol of their salvation. For quite some time, Ian and I sat quietly in the tunnel connecting Bet Gabriel-Rufael and Bet Merkorios, listening to the timeless chanting of pilgrims passing through in the dark. We ended up taking a wrong turn in one of the black tunnels, and found ourselves deep underground in the middle of a centuries-old Christian ritual.

There are some things words can’t describe, so I made a short video — narrated by Haile Abera — to loop you in on what we saw, and what it meant.

QUALITY, NOT QUANTITY

You may feel pressure to see all 11 of the rock-hewn churches, but I can definitively say that taking your time and absorbing Lalibela’s offerings creates a far more memorable and respectful experience than rushing to check off every church on the list. Ian and I only made it to three of them, but we spoke with pilgrims, got lost, found our way into an underground ceremony, touched the walls, felt the carpets, and basked in what was ultimately, one of the most inspiring and stirring travel experiences of my life. What kind of faith inspires someone to chisel by hand a 63 foot church into the ground? To walk for months on end with little food and water just to pray somewhere different? There was something these pilgrims understood about faith, life, spirituality, love and vitality that I simply didn’t. Perhaps one day I’ll see the world as they do. I hope so.

I don’t usually recommend that people skip out on supporting local business, such as hiring a tour guide, but I’ll make a special exception for Lalibela. I strongly recommend that you tour the churches alone. As Ian and I wandered through them, we felt sorry for the tourists next to us, who were missing out on what was going on around them because they were listening to a tour guide explain the paintings and architectural style of the churches. They packed up and moved to the next church on the tour guide’s schedule, undoubtedly trying to squeeze all 11 into a day. Take Lalibela at your own pace, and research the paintings later. Be in the moment. Look, listen, feel and reflect. If you can, go around Christmas (Jan. 7 in Ethiopia), when the pilgrimage reaches its peak. If you do want to hire a guide however, they are available everywhere in Lalibela at any time for 600 Birr per day (negotiable).

NEW YEAR’S EVE

We spent as long as we could in the rock-hewn churches, stopping only for a brief lunch at Abayneh’s restaurant, and to buy a beer for my translator, Haile Abera. That evening was the end of 2014 and the start of 2015, and Ian had purchased tickets to an international buffet dinner at the beautiful Ben Abeba restaurant on top of a hill north of town. We took a tuk tuk to get there, paid about 530 Birr each for the meal (a real splurge), and watched the sunset with a veritable smorgasbord of food from all over the world. We had beer, wine, dessert, coffee and sugared popcorn, and enjoyed a bonfire until close to midnight. It was a fine end to one of the most fantastic years of my life so far, and a classic Rogers and Hammerstein moment.

Know Before You Go — Lalibela

Travel Tips

- Bring a flashlight to Lalibela to help you navigate the tunnels and churches.

- Photography is permitted in the rock-hewn churches, but try to be as respectful as possible while taking pictures of the pilgrims. They allow it as part of your entrance fee (they know the money goes towards the church preservation, the priests, and community), but remember this is a place of worship. Avoid flash photography as it damages the ancient paintings within the churches.

- Try to visit as close to Christmas as possible, and without a guide so that you can enjoy the experience at your own pace. Make sure to invest elsewhere in Lalibela’s economy: Try a traditional Ethiopian coffee ceremony, shop at a nearby curio shop, and eat at local restaurants.

Where to Stay

- The Aman Hotel in town is a quiet, plain, budget accommodation with double beds for roughly 450 Birr per night. I’ll speak very highly of its customer service, as the owner switched our rooms free of charges to accommodate bedding requests, and found me a translator for my interviews, last-minute at a very reasonable price. He did all of this for free, and I promised I would give him glowing reviews on this website. The Aman is also conveniently located in the centre of town, close to restaurants, juice bars, shops, and the rock-hewn churches. WiFi is included in the room rate.

Day 13: Lalibela to Dire Dawa

It was a bittersweet leaving Lalibela. On one hand, I was thrilled I had been able to speak with pilgrims and gain a special understanding of their journey through interviews, but on the other hand, I knew that few other adventures would ever be as eye-opening or impactful. What could Dire Dawa possibly offer us after 13th century churches and a pilgrimage nearly 1,000 years old? Either way, I was pleasantly surprised by this eastern Ethiopian city, which I landed in around 2 p.m. on the very first day of 2016.

Dire Dawa was founded in 1897 and is the fourth-largest city in Ethiopia, with more than 600,000 residents. Tired and cranky, right away, Ian and I got into a bit of a scuffle with the airport cab drivers, who wanted to charge us a truly insulting rate to take us to the Ras Hotel, which is less than a 15 minute walk directly from the terminal (and should only cost about 15 Birr).

KAZIRA AND MEGALA

There isn’t much to see in Dire Dawa in terms of tourist attractions, apart from the old Imperial Railway Company of Ethiopia (which isn’t really worth the entrance fee) and a few busy, messy markets where traditional cloths, plastic home decor and cookery are sold in bulk. We quickly found however, that Dire Dawa wasn’t about the tourism checklist — it was about experiencing the feel of a city, like so many in Ethiopia, caught in between past and present. In Dire Dawa, these two proverbial time zones are physically divided by the Dechatu Wadi river, which runs between the city’s two different settlements. To the northwest lies the globalized ‘new town’ of Kezira, and to the east lies the more colourful ‘old town’ of Megala. We wanted to start in Megala, so we crossed the Dechatu river, which at this time of year, was dried up, full of garbage, and being used as a soccer pitch.

Megala had a distinctly Arabic feel to it and was home to more Muslims that we had observed anywhere else in Ethiopia. We attracted quite a few stares; it was a poor area and I had never seen so many khat–using men and children living on the streets among heaps of trash. They were as kind and friendly as anywhere else in Ethiopia — happy to offer directions in whatever English they could, and to have us over for coffee and sugared popcorn. We bought a custard apple and walked through the streets, dodging mules and goats along the way. We found lots of barbershops, carpet traders and fabric stores, and an old junk yard where ancient European cars collected rust (specimens that Ian, as an automobile enthusiast, had long believed extinct). After wandering around for a few hours, we decided to partake in the local past-time, and bought a bag of khat to chew after dinner.

CHEWING KHAT

Khat is a flowering plant native to the Horn of Africa and its use as a social custom dates back thousands of years. It’s legal in Ethiopia and its effects are very mild. We paid 20 Birr for a large bag of it, and I was eager to understand why it had so many people spending their days with open sacks of it at their feet. The sight of two ferenji walking around town with a big bag of khat, however, was enough to send most people into stitches. I swung it over my shoulders, just to be dramatic, sending some into further fits of laughter, while others walked over give us handshake or high five. We walked back towards the hotel, had a quick pasta dinner at the Paradiso Restaurant, and stopped at a bar to chew. We bought some strawberry and banana gum from the sweet box children patrolling the square, and chewed it along with the leaves to curb its bitter flavour.

We spent the next few hours enjoying beers (our first taste of the malty Harar stout, which soon became our favourite), and chewing on the bright green leaves. In the end, I decided, their soothing, relaxing effect wasn’t worth the effort required to obtain it — you have to chew quite a bit to feel anything, while putting up with a relatively unpleasant taste. You also have to keep the leaves bunched up in your cheeks to soak up the juice, which makes everyone look a bit silly as they struggle to converse with a mouthful. In the end, the effects of the khat were almost unnoticeable; we were a little bit more mellow and talkative, but otherwise quite sober and alert. Around midnight, we decided to have a second round of New Year’s celebrations, took a tuk tuk back to the hotel (40 Birr), and packed our bags for our trip to Harar.

Know Before You Go — Dire Dawa

Travel Tips

- Don’t go into Dire Dawa with high expectations. It’s a city for appreciating the little things, like not knowing how to eat a custard apple, watching kids play soccer on the road, and trying to figure out who cooks the best beans on the street. One day is enough time here, but if you’re pressed for time, give it a miss.

- If you’re nervous about chewing khat, do it somewhere safe, close to your hotel. If it sounds like they’re charging you a lot for the leaves, they probably are.

Where to Stay

- The Ras Hotel, though slightly overpriced at 320 Birr per night, is a comfortable hotel close to town and the airport that has large beds, semi-functional bathrooms, and a bar in the lobby. WiFi not included.

Day 14: Dire Dawa to Harar

Despite having had a bit of late night, Ian and I were up bright and early for our trip to Harar, a small city roughly 55 kilometres southeast of Dire Dawa. We had a breakfast of bread and ful from a woman on the street, who was cooking on an overturned bucket between cars near the Dechatu Wadi bridge, and caught a minibus around 9 a.m. for 40 Birr per person. The two-hour to Harar drive was beautiful, and meadows, farmland, small villages, and ruins whizzed past us on the rocky road to the city.

Though Harar (locally known as Gey) didn’t have the same historical or scenic wow factor as Lalibela or the Simien Mountains, it certainly had the most appealing vibe out of everywhere we had stayed. Life there just seemed more energetic, from the clothes people wore to the fabrics, mattresses and treats displayed in shops throughout the neighbourhoods. The residents of Harar had taken extra care to beautify their city too: The town’s market was decorated with party flags, food stalls were draped with patterned cloths, and people stamped yellow, blue and red beer caps into the sidewalks just to brighten up the dirt. People were truly animated here, and Ian and I were satisfied doing little more than walking around, taking photos, and drinking mixed juice to pass the time.

FERES MAGALA

Our first stop in Harar was the town square of Feres Magala, which is marked by a conspicuous monument dedicated to those who died fighting against Menelik’s conquest of Harar. The hustle and bustle here truly overwhelmed the senses: Kids played tag in the cobblestone streets, meat hung from hooks in butcher stands, and livestock ran hurriedly by carrying bundles of wood, wheat and tef.

Men chuckled happily over beers on patios and women greeted customers warmly as they lined up to buy everything from spices to sunglasses. Unlike the segregated settlements in Dire Dawa, Harar felt like one big community: The people referred to themselves as the Gey ‘Usu (People of the City), they spoke their own language, Harari, and at one time in history, they even had their own distinct currency. Also worth checking out near the square is the famous Harar Gate, which was put in place by Ras Makonnen, the first Duke of Harar, in 1889. From Feres Magala, Ian and I walked to Harar Jugol, the historical highlight of the city.

HARAR JUGOL

Despite the dominance of Orthodox Christianity in Ethiopia, Harar is actually the fourth holiest city in Islam. At least 82 mosques and 102 shrines are squeezed into the town, which lies between the country’s coastal lowlands and central highlands. Harar Jugol, the old walled city, predates the 13th century and its strategic geographic location led to its development as an important centre of Islamic culture and commerce. It is sometimes referred to as “The City of Saints” in Arabic, and was recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2006.

Ian and I had no trouble getting lost in Harar Jugol, where nearly 370 alleyways are packed into one square kilometre. We enjoyed the traditional Islamic architecture mixed with bits and pieces of Western culture, which always seem to infiltrate even the most remote of places. Here, a few children posed enthusiastically for photos, held our hands and followed us through the alleys until their older siblings shouted at them for ‘disturbing’ us, and marched them straight back to their gated homes.

Before leaving, we passed by the bright green Tomb of Sheikh Abadir (one of the most important preachers of Islam in the region), where worshippers still stop seeking solutions to the struggles of everyday life: Financial concern, illness, family crises, infertility. Lonely Planet writes that if their prayers are answered, “many devotees return to make gifts to the shrine, usually rugs or expensive sandalwood. The tomb has become an important centre of pilgrimage, especially for those who cannot afford a trip to Mecca.”

CENTRE TOWN

A short distance away from the old walled city is a polished main strip where youth congregate for food, drinks, shopping and a discreet version of dating that involves handholding when no one is looking. This is where most of the hotels are located, and where restaurants light up at night with neon. You can buy almost anything in this busy part of town, from skinny jeans and remote-control cars to cell phones and sugar cane. Cars and mule carts clang noisily on the streets here, and young men with vats of cooking oil sold chips and ketchup wrapped up in newspaper for 5 Birr a piece. While sitting at a parlour with a juice, Ian and I met a kind young mother who invited us for shisha in her home in exchange for 20 Birr. Happy to get off the beaten track a little, we followed her into a slum near the town centre, and into a small shack with a curtained door.

GUESTS FOR SHISHA

It was a one-room residence with a small tube television, a few possessions, and a number of carpets and pillows on the floor in place of beds or a couch. The woman, who couldn’t have been older than 22 or 23, whipped up a homemade hookah using a water bottle, and passed it over as she opened a bag of khat for herself.

One of her friends came over, and the four of us (unable to communicate in either English or Amharic), sat awkwardly around the television watching an Ethiopian talent contest. The mother’s two-year-old, who was crawling around shack, peed on the floor, and we all smiled, sharing the moment as best we could. When it started to get dark, we bit her adieu, thanked her, and rushed back to our hotel, not wanting to miss one of Harar’s most popular tourist attractions.

FEEDING THE HYENAS

I would never want to cross path’s with a hyena in the wild. They’re dangerous pack hunters and I’ll never forget the first time I saw one gnawing ferociously on a zebra carcass in Kenya. In Addis Ababa, hyenas — considered a vicious pest — have been known to scavenge near local homes, and in times of scarcity, feed on the homeless. Yet more than 500 kilometres away in Harar, the animals have had a peaceful presence for at least 500 years. Feeding them leftover meat was once an important ritual for Sufi Muslims, but today, hyenas help sanitize the city by feeding on organic refuse. They’re also an important source of income for ‘hyena men,’ who tempt them with bits of mule and cow hide for 20 Birr per visiting tourist. Read more on the history here.

As the sun had dipped below the horizon around 7:30 p.m., Ian and I paid a cab driver 130 Birr to take us to a hyena man, wait for us, and return us to our hotel. We were happily led into a pitch black field in the middle of nowhere, where, through the feeble lights of our cell phones, we finally laid eyes on a pack of spotted wild hyenas. We lined up one by one with several other tourists for an opportunity to feed them, and despite being used to this daily ritual, the hyenas remained quite skittish around anyone who wasn’t the hyena man or his young apprentice. When my turn came up, I managed to pet one of braver ones, who took a piece of cow flesh directly from the stick I held with my teeth. It turns out, the hyenas of Harar are more like chubby, unfriendly puppies than vicious scavengers. It was a special experience and I was glad we had included this city in our trip.

Day 15: Harar to Dire Dawa

RAS TAFARI’S HOUSE

Our second day in Harar passed much like the first. We walked around for several hours taking photos and people-watching, and picking up mixed juice wherever we could. Early in the morning, we went back to Harar Jugol to visit Ras Tafari’s House, one of the only ticketed attractions open on a Sunday. We paid 50 Birr for entry into the big white building, which was once the honeymoon home of Emperor Haile Selassie I, and bears his pre-coronation name. Haile Selassie is widely recognized as a divinity of the Rastafari religion, which was founded around 1930 in Jamaica at the time of his coronation.

According to believers, he is the “God of the Black Race” with lineage tracing back to King Solomon and Queen Sheba, his death was a hoax, and he is now arranging for expatriated persons of African origin to return to heaven in Ethiopia. I wasn’t sure how any of this history had churned out stripes, weed and Bob Marley, but I enjoyed comparing Rastafarianism as it is experienced by African followers with the way it is portrayed by mainstream media in the West. Rather than containing information about this movement however, Ras Tafari’s House is actually the site of the Sherif Harar City Museum, which houses a private collection of weaponry, coins, jewellery, household tools and traditional clothing. It’s worth stopping by for the simple reason that there isn’t much else to do in Harar once you’ve done a solid walk-through of the city. After a short visit, we walked back to the minibus station in the centre of town, and hopped back on a minibus towards Dire Dawa.

Know Before You Go — Harar

Where to Stay

- Tewodros Hotel (+251 256 660 217) is a cheap, rundown accommodation that offers sunken-in beds, the occasional cockroach, and dysfunctional bathrooms for about 200 Birr per night. It’s worth it however, for its proximity to a garbage dump, where hyenas are usually visible early in the morning and can easily be heard cackling at night. Check out the soccer pitch around 9 p.m. to see them for sure.

Travel Tips

- Catch an early morning or afternoon minibus to Harar to make sure you arrive in the city during daylight. This minimizes your risk of robbery.

- If you’re a ferenji, conductors on the minibus may try and charge you extra to get to Harar; pay attention to what the other people on the bus are paying and don’t be ripped off!

RETURN TO DIRE DAWA

We returned to the Dire Dawa feeling full. Our memory cards brimmed with more than 2,000 photos each, I had a notebook full of memories, and we had found more meaning and wonder in Ethiopia than we ever could have predicted. We had scaled a mountain in the company one of Earth’s rarest animals, viewed the bones of one of humankind’s oldest ancestors, and witnessed a 700-hundred-year-old pilgrimage ritual that few outsiders knew existed. We had paused at the foot of ruins that nearly predate the Bible, gone face-to-face with one of Africa’s most dangerous animals, and been inspired by the stories people who had lived through extraordinary hardship. On our last full day in Ethiopia, Ian and I weren’t quite sure what to do with ourselves, so as per usual, we went for a walk.

Our 15th night in Ethiopia was defined by some of the best street food we had tasted so far, cooked by a Somali woman outside a bakery in central Dire Dawa. We shared a few laughs with some of her patrons, who were surprised to see two ferenji crouched on a wooden bench on the street digging into a bowl of beans. We had a few Harar beers at the fancy Selam Hotel, which even let us take a few back to our own hotel with us, as long as we paid the bottle deposit. We returned to the Ras Hotel, where we had stayed two nights ago, played a few rounds of cards and turned in.

Day 16: Dire Dawa to Nairobi

After one last hearty breakfast at a roadside stall, surrounded by roosters and whiny cats, we caught a tuk tuk to the airport for our morning flight from Dire Dawa to Addis Ababa. Of course, luck would have it that all of our connections, which had gone smoothly throughout the entire trip, would be delayed on the day of our return to Kenya, and our flight to Nairobi was cancelled by a complication at JKIA airport. While this meant we got another night in Ethiopia — paid for by the airline at the spectacular, high-class Nexus Hotel in Bole — it also meant prolonging our exhausted, travel-weary state by one more day. We spent hours on Day 16 waiting in airport lobbies, playing cards and watching the news, until finally, we were able to settle in Addis for the night.

After a sumptuous buffet dinner at the Nexus, for the first time on the trip, I took a hot shower with proper water pressure. I slept in a regal red room with plush pillows, and a feather duvet, expensive art work, and a cable-connected television that picked up more channels than I had grown up with as a child in Canada. There were no cockroaches or flickering light bulbs, and the room came with actual slippers rather than those generic plastic flip flops that come in many cheap African hotel rooms, and never fit anyone under six feet tall. I can’t say we didn’t end the trip in style, but I can say that the superfluous luxury felt a bit uncomfortable after more than two weeks on the road with moth-eaten bed sheets. Ethiopia was the adventure of a lifetime, and I hope after reading this, you’ll consider making your own trip to one of the beautiful and historic countries in the world.