October 2017

A MUDDY ESCAPE AND A COHORT OF WOMEN

After reading too many cliché blog posts about blistering heat in Central America, I vowed not to start this one by describing waves of humidity, beads of sweat or any other form of moisture as I stepped off the plane in Tegucigalpa.

Instead, I’ll start with me, wandering around the Honduran capital wearing an unseasonably warm denim jacket and the most intimidating facial expression one can muster after 24 hours without any sleep.

(The irony of the first paragraph is not lost on me).

I arrived in Honduras on Oct. 19, 2017 with a bright green, 50-litre knapsack strapped to my waist and a worthy head of airplane hair following transfers in Toronto and San Salvador. It was a last-minute work trip, and I had only enough prep time to dig up the following facts about Honduras: its government is notoriously corrupt, held captive by organized crime and clandestine power groups; its capital city has claimed the world’s highest murder rates; and it’s one of the deadliest and most dangerous places to be an activist, a journalist or a woman.

I, naturally, was at least two of the three, and there to investigate human rights abuses tied to state corruption and international energy corporations. I pored over statistics from my hotel room: one woman murdered every 16 hours. More than one environmental activist murdered every month. Unconfirmed rates of incarceration for reporters, and at least 69 dead since 2001. It’s unfortunate this negativity dominates online literature about Honduras, a truly beautiful country whose spirited people have much more to offer than crime stats.

Nevertheless, I put my guard up in Tegucigalpa, wearing the don’t-mess-with-me-face I had mastered long ago in Kenya. In about a day, I would link up with an inspiring cohort of women activists, philanthropists and Nobel Peace Prize laureates from around the world, but until then, the aviators were on, the hair was tied back and the reporting equipment was safely stowed from public view.

It was the beginning of a Central American adventure that after two, weeks of reporting, would send me bouncing off a rooftop trampoline at midnight in Guatemala, hitchhiking to the surf in El Salvador, and sledding down a volcano in Nicaragua. Below, you’ll find an account of my experience as a journalist in Honduras, along with a few useful tips, should you choose to travel there.

Day One: A stroll through Tegucigalpa

If you walk around Tegucigalpa, be prepared to feel the burn. This stunning, highland city is surrounded by lush green mountains, and its roads are steeper than any I’ve seen — and I’ve been to San Francisco. The commute is aggravated by a lack of urban planning, which has more than 400,000 people battling gridlock in cars, tuk tuks, on bikes and on foot, in temperatures that sometimes exceeds 30°C.

A FEMINIST UPRISING SHAKING THE CAPITAL

The city is divided by the Choluteca River, which separates it from its sister city of Comayagüela. Brightly-painted houses, metal sheet shelters and gated complexes with flowering creepers are among its residential establishments, divided by wealth. In the downtown core, you can lose yourself in plazas, shopping centres and restaurants if your pockets are deep, but for many of Téguz’s 1.2 million residents, who live in informal settlements, such swanky pitstops are out of reach.

I walked around an area called Colonia Palmira, where omnipresent gun-toting guards provide some semblance of safety. This is where many of the city’s embassies are located, and here, I found glorious signs of political resistance between billboard ads for Pizza Hut, Forever 21 and McDonald’s new Jolly Rancher McFlurry (apparently a marketable flavour in Honduras). Contraceptives graffitied to brick walls promoted reproductive rights against a total government ban on abortion, while spray-painted superheroes endorsed anti-corruption activism.

Elsewhere in the city, murals paid tribute to beloved Berta Cáceres, a murdered Indigenous activist whom the Honduran government failed to protect. All signs pointed toward an Indigenous and feminist uprising that is shaking traditional systems of power — a movement I chronicled for the National Observer.

READ: Women in Honduras are leading a rights revolution. How many lives will it cost them?

With a passion fruit smoothie in hand (69 Lempiras from a nearby café), I continued my march into residential Téguz. The public bus horns had cartoonish melodies that promptly sounded at the first sign of unwanted service from squeegee boys. Elsewhere, clowns and jugglers tailed uniformed students buying sweeties from chip, fruit and flower stands. It certainly didn’t seem like a city whose murder rate is among the highest in the world, but few cities reveal their character after just half a day’s walk.

In short, be cautious in Tegucigalpa, but don’t make sweeping assumptions about the city or its people based on the violence detailed online. I know women who live here, walk to work here, and love their lives in the Honduran capital. But as a first-time visitor, I’d stick to the beaten path.

HONDURAN HISTORY “THE SAME AS A TEAR”

Later that evening, I met the women with whom I’d be travelling: a jaw-dropping assembly of international feminist, peace and democracy powerhouses, led by Nobel Peace Prize laureates Tawakkol Karman of Yemen and Shirin Ebadi of Iran.

They were in Honduras to bear witness to injustice, and use their prominence to amplify the voices of local women human rights defenders. Read more about the Nobel Women’s Initiative here. We were told over dinner by local activists that Honduras has been “kidnapped by its political system,” and is the most unequal country in the region for women after Haiti.

“The history of Honduras, unfortunately, could be the same as a tear,” said Daysi Flores of Just Associates MesoAmerica, revealing that 98 per cent of murder cases involving women are never investigated.

We were saddened and angered, but not surprised, and glad we were there to offer our emotional, spiritual and professional support. I would later learn that our inaugural meeting coincided with K’at, the spider, on the Mayan calendar — a day for solving problems, undoing the knots of life, making friends and forming new unions in a group. It would not be the last time the Mayan calendar surprised us during our time in Central America.

Day Two: The forests of Río Blanco

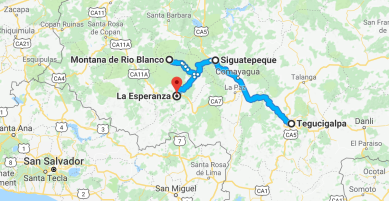

Tegucigalpa wakes up around 5 a.m., which is when our jet-lagged delegation shuffled blearily onto a bus bound for Río Blanco, roughly four hours by road in the Department of Intibucá. As the sun peeked over the mountains, dumpster divers were already at work on the outskirts of town, while commuters waited for buses into town. A few joggers even braved the cool morning air.

The winding road out of Téguz provides a more complete picture of life in Honduras than the city does. After passing a waterpark, Chinese villa, U.S. military base, and Wendy’s Restaurant in the middle of nowhere, our landscape shifted to one of auto junk yards, maize and coffee plantations with an unending backdrop of bright green hillside. We pulled over twice before reaching our final destination — first, to be informed that we were in Indigenous Lenca territory, and second, because our bus would soon become stuck in the mud if it continued its uphill drive.

We split into smaller groups and I hopped in the back of the nearest truck.

We were on our way to the Gualcarque River — the sacred lifeblood of the Lenca people, and the river that award-winning environmentalist Berta Cáceres died to protect from a Honduran hydro company. For more information on her murder and the people behind it, read this jaw-dropping New York Times investigation.

“BERTA DID NOT DIE, SHE MULTIPLIED”

We were greeted in Río Blanco by more than 100 Lenca activists in a forest base where they keep careful watch over the river. The hydro project has been abandoned in the wake of Berta’s murder, but the government-issued concession for the property has not yet been withdrawn. At the top of the hill, a small flowered altar lay propped up against a tree, bearing images of their slain Indigenous heroine. Community leaders made speeches, elders led prayers and children lit candles in Berta’s honour. They chanted, in Spanish, again and again: “Berta did not die, she multiplied!”

I interviewed some of the women, who told harrowing stories of midnight raids on their villages, machete wounds, and incarcerated or disappeared friends and family. They were targeted, they said, both for their association with Berta and their peaceful opposition to the hydro project. Some had gone into hiding to protect their families; others had been arrested and charged. Of her own mother, who is in charge of finances for the advocacy group co-founded by Berta, nine-year-old Alma Edith Sanchez Dominguez said:

“She’s a woman who struggled with Berta and I like it. It makes me want to be like her.”

After a short ceremony, we passed around beans and rice from a communal pot. Then we started the sweaty hike to the Gualcarque River — a path marked by crop fields, abandoned hydro infrastructure, and the graves of those killed in the movement to protect the land and water.

A NEAR-MISS ON THE MOUNTAIN

It was a sombre day that ended with a bit of an adrenaline rush. We were sitting in the bus with some Lenca men from out of town, when it started sliding uncontrollably down the slick wet mountain. We hopped out quickly as the bus continued to slip on switchbacks without protective railing. Our guests heaved the bus out of the mud and tried to keep it from teetering over the edge of the cliffs — a feat that nearly cost two or three of them their lives as the vehicle crushed them into a curve. Men on horses jumped out of the way and we walked in the rain until more trucks could come to pick us up.

I stayed in this truck, sandwiched between Tawakkol, her husband and her translator, until we reached La Esperanza, the hometown of Berta Cáceres. Her second-youngest daughter, Bertha Zúniga, and her mother were waiting to meet us for dinner at La Hacienda restaurant. It turns out Berta came by her activism honestly — her mother served four terms as the local mayor and ran for congress during the 1980s. It was an unprecedented move for a woman, who was so determined to fight injustice, she sold tortillas on the streets to fund her campaign. Today, Berta’s daughters have taken up the fight, and one was elected to Congress in the recent federal election.

After a delicious, smoky meal of fried plantain and anafre — a Honduran bean and cheese dip served over fire, we all hit the sack. I was instructed by friendly English signage at our hotel, La Posada Papá Chepe, that a “smile costs less than electricity and gives light,” so I should let water “escape” because “saving is winning.” The hotel is working to “improve our of ambient,” the sign read.

Day Three: “A citizenship of fear”

I awoke the next morning to the sound of church bells — an unusual ring reminiscent of the bus horns in Tegucigalpa. It was Sunday morning, and in the hotel garden, a breakfast of pureed watermelon and pancakes was waiting.

I stepped outside into the Parque Central to a lively scene: children led by local youth groups danced, blew soap bubbles and played ring toss, while elders and families observed the commotion with bits of breakfast in their laps. People fed pigeons by the golden square fountain, and listened to hymns from the church next door. I absorbed it all happily, chewing on fresh lychee fruit (L 10 for half a bag) as I wandered the markets with Pamela Shifman, executive director of the NoVo Foundation, and a member of our delegation.

A HIKE TO LA GRUTA

After an hour or so, we found our way to the northeast end of town, where the picturesque La Gruta lies etched into a hill called La Crucita. The stark white hermitage is dedicated to the Virgin of Immaculate Conception, and was apparently built under orders from J. Inéz Pérez, who hid in the cave to escape his enemies, likely sometime between 1920 and 1944.

We climbed up the shrine’s steps and behind them to reach the top of the La Crucita, which offers an unparalleled view of La Esperanza and its high-altitude, mountain valley landscape. It’s a colourful, quaint little city with an extraordinary feeling of warmth, given its renown as the coolest city in the country.

When we got back to the hotel, a few girls rushed over to sell us baskets I had seen them quietly obtain from the hotel gift shop earlier that morning. It was a clever tactic — foreigners are more likely to buy from local children than a hotel, and the girls probably got a cut of the sale afterward. Well played.

PRE-ELECTORAL STRAIN IN HONDURAS

We were seen out of La Esperanza by a rambunctious parade of red and white — the colours of the official opposition Liberal Party of Honduras, which sought to oust to President Juan Orlando Hernández from power. We were in Honduras the month before a federal election, just weeks before its results would hurl the country into its worst political crisis in a decade. Hernández was re-elected against a constitutional ban on presidents serving a second term, and post-election violence has since left more than 30 people dead on the streets.

The election put an extra strain on our trip, impacting both the politicians we could speak to, and what our two Nobel laureates could say in public. Neither could be seen to endorse any particular candidate or party, so they focussed their speeches on the promotion of peace, respect for democracy, and adherence to international human rights standards.

By the time we got back to the capital — full of malanga chips from our pit stop in Siguatepeque — we were more than an hour late for our conference with women human rights defenders from across the country. Many were fighting their own battles to protect land and water from mining companies, keep foreign seeds and chemicals away from their crops, and protect each other in a country where more than 5,000 women and girls have been murdered in the last 15 years.

“What we’re talking about is a citizenship of fear,” said Suyapa Martínez, co-director of the Center for Women’s Studies — Honduras, rhyming off an unthinkable list of statistics on violence against women. “In this country there is absolutely no arms control.”

It was, at times, a tearful endeavour. To the right of Suyapa, tributes to missing and murdered women activists, including Berta Cáceres and a number of children, added weight to the evening’s heavy proceedings.

“Our land, our cornfields have become a battlefield,” said added campesina activist Jessica Sánchez. “They colony may have taken our history, but they did not take our roots.”

More than 7,000 women have been criminally charged in Honduras for their work in human rights advocacy.

Day Four: Politics in the Capital

I awoke on my fourth morning in Tegucigalpa to a wonderful sunny sky, a rare treat at the peak of the rainy season. At this point, I had learned that to ask a server for café con leche, is to receive a small cup with little coffee and mostly milk, so I asked for café con “poquito, poquito” leche as I tucked into the usual: fried eggs, refried beans, a bit of cheese and crema.

I ate lightly, since we had breakfast meeting with Honduras’ Congressional Gender Commission (Women’s Caucus) and Inter-Agency Gender Group. I was thrilled with the prospect of speaking to politicians in a country known for corruption, and hearing their perspective on the human rights crisis they were charged with resolving.

“BOTTLENECKED” BY MEN IN CONGRESS

I found no quarrel with this group of elected women who, for the first time in Honduran history, were working across party lines to elevate the status of women nationwide. They did not deny that the government had corruption issues, or that women were murdered daily under their watch. But progress is slow and the solutions are complex, they revealed, in a patriarchal culture of machismo — all the rules that govern a society made by men “who consider themselves to be the owners of women’s bodies,” as one woman put it.

As female politicians, they faced regular harassment, and even when they managed to put forward a bill in support of human rights, said it was often “bottlenecked” or reversed behind closed doors by their male colleagues in Congress.

“Honestly, in many ways we achieved power, but were deceived,” said Yadira Bendaña, president of the commission, naming femicide investigations as an example.

It took months of work, she explained, to pass a proposal to create a special investigative unit for femicides after being basically “ambushed at the table” by their male counterparts. In the end, the unit was launched in 2016, but with a paltry budget of $1.5 million.

As they discussed the barriers toward progress, I remarked on the contrast with our visits to the countryside earlier in the week. Today, we shared a meal with well-dressed women in lipstick and jewelry, who checked their smartphones constantly. Only days before, we had shared a similar meal with the Lenca women in Río Blanco — most of whom carried a child in each arm as we ate from a pot on the ground. Their settings couldn’t be more disparate, yet both these groups of women worked toward a common cause.

ASLEEP AT THE WHEEL

It was a meeting-heavy day. That afternoon, we chatted with the special representative of the Secretary General of MACCIH, the Mission to Support Corruption and Impunity in Honduras. It’s described as a relatively “toothless” body, whose investigative work is being actively hampered by the government. While they spoke vigorously about the problems and need for change in Honduras, it seemed to me that they hampered their own work as well — during our meeting, one of MACCIH’s high-ranking members fell asleep.

After a quick lunch of seafood and hibiscus juice at El Morito, we met the country’s vice-minister of human rights and justice. She was quick tout government successes before acknowledging that more work needed to be done to protect women, girls, journalists and activists in Honduras. Watch my video below, published in the National Observer:

Our last meeting was with members of the G16 and the representative of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, who pursued various diplomatic options to reduce corruption and impunity in Honduras. The was discernible frustration in the room — forced to weave through complex bureaucratic hoops with a government that has not been fully co-operative, they revealed that international community has placed its hope for Honduras in MACCIH.

That evening, we attended a pleasant diplomatic reception hosted by the Embassy of Canada, then returned to the hotel for a small celebration on our final night in Honduras. We gorged on anafre, catracha sushi (catracha/o is a non-offensive word for Hondurans) and the country’s Imperial beer, which I found unimpressive. We discussed all of our mission’s findings to date, and decided that someone needs to invent a smartphone app that generates witty comebacks for sexist comments from men.

Day Five: En route to Guatemala City

Our last day in Honduras was bittersweet. We said goodbye to new friends and allies who worked tirelessly during our stay to ensure all went smoothly, with the knowledge that our journey would continue in Guatemala and the numbers in our delegation would grow.

I would miss a good number of them, especially Honduran journalist Sandra Maribel Sánchez — an indefatigable, unbreakable woman who has run rugged uphill miles as a reporter, just to gain an inch of respect in spaces dominated by men, and earn the freedom to cover progressive social issues. Read more about Sánchez in the article I wrote for the National Observer:

Blackmailed and beaten: the life of a female journalist in Honduras

Our Nobel laureates, Shirin Ebadi and Tawakkol Karman, held a press conference for Honduran journalists. Some tried to corner them into commenting on the national election, but they coolly directed their answers toward the right of Honduran people to justice, safety and equal opportunity.

Outside the room where this took place, I met a charming elderly woman named Katia Cooper, who — upon hearing I’m Canadian — begged me to deliver her best wishes to celebrated Canadian filmmaker, climate activist and author Naomi Klein. She was a big fan of The Shock Doctrine, she explained, and regarded Naomi as personal heroine. Katia said she only wished the book was less expensive, so it could be stocked in Honduran classrooms.

She left me with a chilling message on corruption in Honduras:

“Corruption has made our people so unable to understand the need for change. They’ve been hungry for so long, it’s hard for them to have the energy to say no to it. It feeds them that day… Corruption works like a Swiss watch. It’s perfect, like a Rolex, so the middle class — it’s what they strive for.”

I sent an email to Naomi on her behalf.

We left that afternoon for Guatemala City. It didn’t go as smoothly as we had hoped — one of our delegation member’s bags were searched due to “suspicious” contents (paper pamphlets for a non-profit) and Shirin was held back by customs of her Iranian passport.

I left Honduras feeling troubled. Corruption, injustice and crime certainly don’t shock, but I admit to being surprised by the boldness of its form in Honduras. In other countries I’ve worked in, efforts are at least made to mask and deny corruption, but here, it was widely acknowledged by elected officials. It seemed as though the people were actively dared to challenge it, and crushed for rising to the occasion.

Know Before You Go — Honduras

Travel Tips:

- Don’t walk around with anything that makes you a target in Tegucigalpa, including phones, cameras or purses. It’s best not to walk alone either, especially if you’re a woman.

- Bring American currency with you, and swap it for Lempiras at your hotel. If you can withdraw at an ATM in the city, even better, since you’ll probably get a better rate. Just make sure you have local currency on hand if you travel into rural areas, where you’re unlikely to find a bank machine.

- There isn’t much English spoken in Honduras, even in the capital. A little Spanish goes a long way, so have a few phrases ready in advance.

- Prepare to encounter brutal traffic in Tegucigalpa, and factor it into the amount of time you give yourself to get anywhere, including the airport.

- For delicious food and an unparalleled view of downtown Tegucigalpa, check out Piso 24 in the Torre Metropolis, and ask to sit on the terrace.

- Print plans and make reservations ahead of time, since foreigners aren’t allowed to purchase local SIM cards, and you may not be able to make use of you cell phone without a pricey international plan.

- Make sure you’re up to speed on what the presence of malaria and Zika virus in rural Honduras.

- I didn’t visit Honduras as a tourist, and recommend scrolling through Wikitravel for a list of the country’s highlights, including Mayan ruins at Copán, scuba diving in Utila and Roatán, and more.

Where to Stay

- The Hotel Honduras Maya is a well-furnished hotel in a safe part of Tegucigalpa. You may want to consider forking out the base rate of USD 90 per night for peace of mind and comfort in a city where it may not be wise to gamble on the cheapest hostel. The Honduras Maya has a swimming pool, WiFi (spotty, at best) and above average restaurants and bars. Get in touch at +504 2280 5000 or info@hondurasmaya.hn.

- Reputable hostels in Tegucigalpa include Palmira Hostel, La Ronda Hostel Tegucigalpa and Hostal Mision Catracha.

- Posada Papá Chepe is a clean, affordable hotel in La Esperanza with rates as low as USD 50 per night, inclusive of breakfast. The WiFi is pretty decent and it’s within walking distance to all of La Esperanza’s major attractions. Call +504 2783 0443 for a reservation.